HOW TO WRITE A PHILOSOPHY ESSAY

By Kyle Strouse

How To Ask Philosophical Questions

In the Introduction, we talked about how philosophy is the study of asking questions. In this section, we will learn what some of those questions are, the importance of asking good questions, the structure of a question, and how to come up with our own.

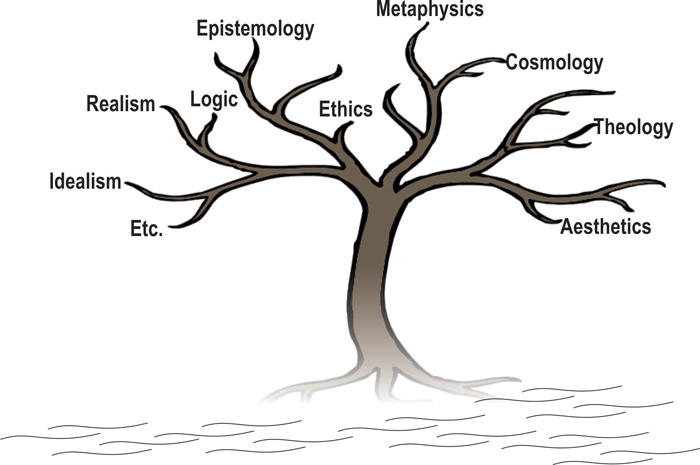

1. The Branches of Philosophy

Before we can start writing our philosophy essays, we need to figure out what, exactly, we want to write about. The problem is that the field of philosophy is vast. Very vast. So vast that two philosophers can work their whole lives and never write about the same thing. For this reason, the field of philosophy is usually broken down into seperate branches of study. Each branch is concerned with different philosophical topics, and as such asks different philosophical questions. For our purposes we will seperate philosophy into 5 seperate branches--keep in mind, however, that there is overlap in some of these subjects, and that some philosophers believe there are more or less categories. These 5 branches are:

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the study of first principles. The subject explores the most fundamental concepts of reality; space, time, existence, the nature of being, etc. If "physics" is the study of matter and its interactions, then "metaphysics" is the study of the nature of matter--of how and in what form matter exists. It is perhaps the most abstract branch of philosophy, yet has also helped lay the foundations for what we know (or what we think we know!) about our universe. If questions like:

- What is the nature of time?

- Why is there something rather than nothing?

- What is a person?

- What is reality?

Interest you, then metaphysics is a good place to start!

Epistemology

Epistemology is the study of knowledge. Epistemologists typically work with the nature of truth, the difference between fact and opinion, and the meaning of rational thought. They also grapple with skepticism, which is the belief that knowledge is impossible to obtain, or at least very limited. Epistemology has a rich history in philosophy--almost every major philosopher has at some point or other grappled with epistemological questions. These include:

- Can we provide a foundation for our knowledge? If so, what is it?

- What does it mean for a fact to be true?

- How can we justify our beliefs?

If the nature of knowledge and reason appeals to you, then give epistemology a try!

Logic

Logic is the study of arguments. It is also unique in that philosophers in every branch (some, perhaps, more than others) use logic to advance the study of their own branches. As such, logic is philosophy's foundation. Philosophers are not the only ones who study logic--mathematicians, computer scientists, and other professionals use logic to draw conclusions. Those who study logic investiagte the relationship between premises and conclusions, rules of deduction, the translation of natural languages into logical languages, and valid argument structure, among other things. If you are intimidated by logic, don't worry! You don't need to be a master logician to do good philosophy, and we will go over the basics later in the tutorial.

Ethics

Ethics is the study of values. It is a broad field, encompassing many different topics. Because of this, philosophers typically break it down into three sub-categories. Metaethics studies questions about ethics, such as

- Is morality objective or subjective?

- What do we mean by 'right act'?

- Is there such a thing as a 'moral life'?

Normative ethics studies questions concerning what values, or right acts, should be. These questions include:

- What makes an act right?

- How does one live morally?

- What are the standards for saying something is 'good' or 'bad'?

Applied ethics is the study of how to act in different situations. These are questions like:

- Is killing ever justified?

- Is lying okay in some situations?

- Should voluntary euthanasia be allowed?

As you can see, ethics is incredibly complex and deals with many different issues. Yet it can also be a very beginner-friendly introduction to philosophy, and many of the questions it asks are highly applicable today. If any of the questions above interest you, look into writing about ethics!

Philosophy of Mind

Philosophers of mind study the nature of the mind. More specifically, they ask questions about conciousness, unconciousness, thoughts, dreams, mental states, the brain, and the relationship of the mind with the body. Philosophy of mind has signifigant overlap with the field of psychology, although philosophers of mind tend to invesigate questions that are more 'meta' than what a psychologist might ask (though this is not always true). Examples of those questions are:

- What is conciousness? What is it made out of, if anything?

- How does a non-physical entity (the mind) interact with a physical entity (the body)?

- Do entities besides humans have minds? Can they ever?

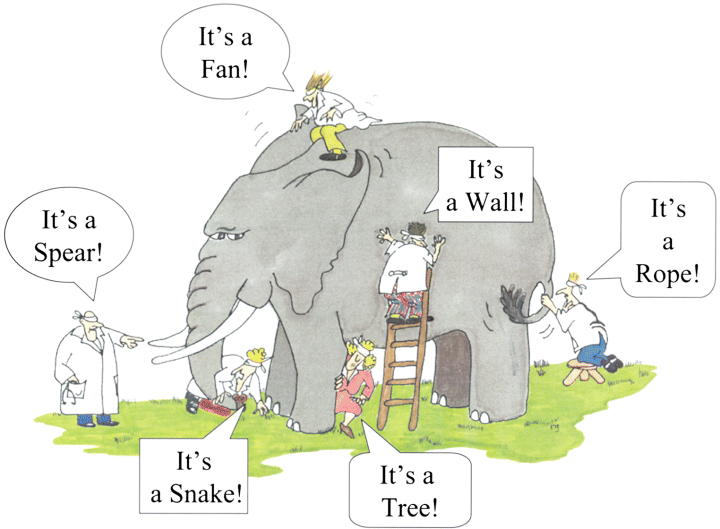

2. Identifying Knowledge Gaps

Now that you are familar with the 5 main branches of philosophy, it's time to start thinking about the kinds of philosophical questions you are interested in answering. The best way to come up with a good philosophy question is to identiy knowledge gaps. Knowledge gaps are the parts of our conceptual models that are missing, fuzzy, or incorrectly put together. For instance, if I believe that I can access the web browser on my computer by typing "google" into a word processor and clicking "enter", then there is obviously a knowlege gap in my conceptual model of how a computer works. Knowledge gaps in philosophy work the same way, the difference being that the conceptual models philosophers are interested in are often much more abstract than those that computer scientists work with. A knowledge gap for a metaphysicst might be how a person that is constantly changing can remain the same through time. Likewise, a knowledge gap for an ethical philosopher could be whether or not happiness is the greatest good. Philosophy is all about finding these gaps in our conceptual models of the universe and trying to fill them in with logic and reason.

To find philosophical knowledge gaps, take some time to observe the world around you. What do you take for granted? For instance, have you been asked to donate to a charity in the past month? Perhaps in the checkout line at a convience store, or by email? Although your response to this question may have seemed trivial at the time, philosophers have been debating for centuries whether or not we have a moral obligation to donate to charity. Many consequentialsts, for instance, believe that we have a moral obligation to perform acts that we would like the rest of the world to peform. Therefore, if you would like the rest of the world to donate to charity at Walmart checkout lines, then you are morally obligated to do so yourself. A hedonist, on the other hand, might argue that morally right acts are those which bring the actor the most happiness. So, if you get a lot of happiness out of refusing to donate to the charities of large corporations, then you would be morally obligated not to donate. A utilitarian, who believes that right acts are those which maximize the total happiness of a population, might take a stance on either side. The point is this; even things as insigifgant as rounding up for charity are fraught with philosophical questions and opinions. Most people navigate through life with a conceptual model that seems right to them, but upon further inspection has many knowledge gaps--like a house with a weak foundation. It is the job of a philosopher to shore up these foundations, to question their conceptual models of what the world is and how it works, and to try and arrive at some fundamental truths.

Challenge

Before moving on, try to come up with a knowledge gap in your conceptual model of the world. What is something you believe but have never questioned? What are the motivations behind some of the routine choices you make every day? After you come up with a knowledge gap, try to find the fundamental truth behind it.

If you need inspiration, try looking at some of the example questions above.

3. Crafting Good Questions

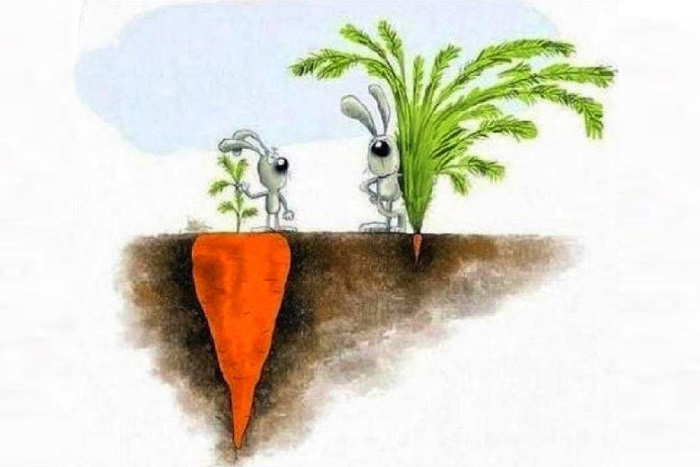

Now that you've identified a knowledge gap in your conceptual model, it's time to target that knowledge gap with a philosophical question. Philosophical questions are important because they help define exactly what kind of knowledge gap we are trying to fill. For instance, a question like what is time? can be difficult for a beginner to answer because the knowledge gap is so complex--to answer it would require an in-depth knowledge of not just metaphysics, but likely physics and epistemology as well. To help create good philosophical questions, keep these two criteria in mind:

Specificity

As questions become more specific, they often become easier to answer. That's because a speicifc question helps narrow the focus of the problem. For instance, the answer to a question like What is a right act? will be much more complex then the answer to Does a poor person have a moral obligation to donate to charity? Although general questions are important and the subject of most groundbreaking philosophical work, it is very easy for a beginner philosopher to get stuck in the weeds.

Applicability

Questions that are applicable to to our real-world experiences are generally more approachable then abstract questions. Let's suppose, for instance, that we have recognized a gap in our knowledge of what the world is made of. Instead of asking What is the world made of?, a question filled with ambiguity, let's ask instead Is the chair that I am sitting on made of the same stuff as the apple that I am eating? A question like the latter helps our mind focus in on something that it is familiar with, while simultaneously building the foundation for answering the first question. Asking questions about real-world experiences to build the foundation for larger and more abstract questions is a technique that philosophers use all the time.

Challenge

Now that you are familiar with the principles of philosophical questions, it's time to come up with your own! As you are thinking about your question, keep these criteria in mind:

- Are you genuinely interested in the answer to your question?

- Does it target one of your existing knowledge gaps?

- Is it both specific and applicable?