HOW TO WRITE A PHILOSOPHY ESSAY

By Kyle Strouse

How to Write

You've learned the basics of logic. You've asked yourself some philosophical questions. And you've researched your field of interest. Now, it's finally time to put your own ideas on paper. In this section, you'll learn some general guidelines on how to communicate your argument in the form of an essay.

1. Outlining

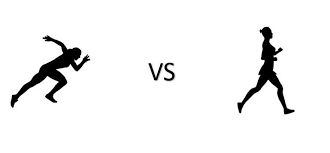

Writing a philosophy essay is a marathon, not a sprint. And like any race, it's helpful to know what your path will be before you start running. Having a plan detailing what you will talk about, even if the plan is very general, can save you an immense amount of time and frustration. For that reason, I recommend constructing an outline before the actual essay-writing process begins.

What is an outline?

An outline is like a skeleton of your paper. It is a document that describes each step of your argument in a general way. Here's an outline for making an omelette:

- Gather eggs

- Crack into pan

- Cook until solid

- Fold over each other

- Serve

This gives us a general guide on how to make an omelette, which we can add to later to suit our own needs and preferences. Similarly, an outline in philosophy is a general guide on how to structure and arrange your argument, which you can tweak as you write to fine-tune your paper.

2. The Essay Form

There are many ways to structure an outline. But perhaps the most popular way in the humanities is the essay form. The essay form is an argument structure that has 6 sections: The introduction; The thesis; The argument; The counterarguments; The refutations; and The conclusion. If you follow this format, your argument will be consistent, concise, clear and comprehensive.

The Introduction

The introduction introduces the reader to your essay. A good introduction tells the reader 3 thrings, and three things only:

- What the question is

- What the answer to the question is

- How the answer will be proven

An introduction should be short and interesting. The first sentence should be a hook, something that makes the reader want to continue reading. Make sure the hook is relevant to your essay though--quotes, or asking the user to "use their imagination" are very cliched. A good hook could simply be the question you are attempting to answer. An introduction should also provide content. Why is the question you are asking interesting? Why haven't others given proper answers? What makes your answer different? These are some of the questions you should answer.

As a rule of thumb, don't make your introduction longer than a few sentences. An introduction that drags on and on can quickly bore the reader.

The Thesis

The thesis, or thesis statement, is a single sentence (or two, sometimes) which tells the reader exactly what you are going to do in your paper. It is always the last sentence of your introduction. It tells the reader your argument, and each step you will take to prove that argument. It's a good idea to keep the thesis neat and detailed--a simple "In this paper I will prove ____ by arguing for ____, ____, and ____" works fine. Here's an examples of a thesis statement:

In this paper, I will prove that knowledge exists by arguing that science relies on knowledge, that knowleedge is true belief, that science is true belief, and that science exists.

Challenge

Before moving on, try to come up with a thesis for your own paper. Think about what the big picture of your argument is, and what steps you will use to back up that argument.

The Argument

The argument is the section where you show the reader, with logic, reason, and evidence, that what you claimed to be true in the thesis is actually true. It should almost always be the longest portion of your paper. Arguments, like other sections of your paper, are split into body paragraphs, each of which should be just long enough to explain the idea you are trying to get across. A good four-step program for constructing a body paragraph is listed below:

- Topic sentence: Tell the reader what your idea is in a sentence or two

- Context: 1-2 sentences for any necessary context

- Evidence: The reasons for why your idea is true

- Summary: 1-2 sentences summarizing what you just argued, and why it is important for the big picture.

Remember to stay on-topic--don't drift into ideas that are not relevant to the big picture in your thesis.

The Counterarguments

The counterarguments section is where you tell your reader about potential counterarguments to your own argument. One of the most important skills a philosopher possesses is the ability to remain open-minded--a philosopher loves the truth, not their own opinions. For that reason, it is vital to acknowledge that there are almost certainly valid counterarguments that others could raise towards your position. By anticipating these counterarguments you do two things: first, you show your reader that you are intellecutally honest; second, you give yourself room to rebut them. By explaining the counterarguments yourself, you get to make sure that your own argument is properly conceptualized while simultaneously getting to respond to these criticisms immediately.

When constructing counterarguments, it is important not to "cheat" your opposition. Don't create strawmen, or arguments that are purposely easy to defeat. Rather you should strive to create the strongest possible objection to your own position--by properly refuting it you will seriously take the wind out of the sails of any potential objectors.

Counterarguments are a very important part of your paper, and as such should take up just a little less space than the argument section. Counterarguments are also constructed in body paragraph form--you can follow the same program for constructing argument parapgrhaphs when constructing your counterarguments.

Challenge

Try creating one argument paragraph for your thesis. Then, try to come up with one counterargument.

The Refutations

The refutations section is where you respond to the counterarguments that you constructed. Typically, refutations point out some flaw in logic or reasoning that the counterargument failed to notice--but if the counterargument is particularly strong, you can modify your current argument to account for it. It is important to be fair to the counterarguments--do not intentionally make the counterarguments weaker in order to refute them.

Refutations take the same form as arguments--your topic sentence should be the counterargument you are addressiong, and how you plan to address it. The length of your refutations is dependent on how many counterarguments you anticipate. If your position is controversial, then it is fine to have a somewhat long section devoted to refutations.

The Conclusion

The conclusion section has two purposes--to sum up what you have just told the reader, and to look forward to the future.

When summarizing, you should keep things concise. The reader may be fatigued at this point if they have paid careful attention to your argument--don't make them work too hard in the summary. A simple restatement of the thesis is often sufficient; tell the reader what the main argument of your essay was, and the steps that you took to prove it. It is also a good idea to mention the counterarguments you addressed, and the refutations you gave to them. Try to not summarize for more than 3 sentences.

When looking to the future, you should keep things even shorter. Tell the reader in 1-2 sentences what you believe the consequences of your argument are. Are certain theories proved wrong because of it? Are there ethical issues? Is there more research that must be done? These are all questions you can answer when thinking about the future.

The conclusion, like the introduction, should never be longer than a paragraph.

Challenge

Try to refute the counterargument that you made. After you're done refuting it, create an introduction and a conclusion for the argument, counterargument, and refutation.

3. Tips and Tricks

If you finished the challenge above, then congragulations! You've just written a philosophy essay. It may be short and a bit unpolished, but that's okay; philosophy is a marathon, not a sprint. Now, all you need are a few tips and tricks in order to combine everything you know into a full-fledged philosophical argument.

Tip 1: Keep Things Simple

There is a temptation, especially after reading philosophy, to use complicated jargon and "purple prose". I reccomend against this. Making things simple will not just help you, it will help your reader. Simplicity keeps things clear, keeps things concise, and keeps things logically consistent. After you've gained some experience it may be useful to incorporate some jargon into you arguments--but for now, just focus on getting your ideas across in a way that makes sense to you, and will make sense to amateurs.

Tip 2: Explain your terms

Keeping with the theme of simplicity, it's a good idea to explain any term that is important to your argument. Are you writing about free will? You should explain exactly what you think free will means. Writing about whether or not dogs exist? You better give an exact definition of a dog. Without precise definitions and explanations, words can start to mean things that we don't intend them to mean. For that reason, make sure you explain all relevant terms.

Tip 3: First or Third Person Are Fine

Philosophy often involves belief. For that reason, it's okay to write in the first person--in fact, you may find it more inuitive than writing in the third. What you should avoid doing is writing in second person. It often sounds informal, and turn off the reader to your argument if it is something they disagree with.

Tip 4: Cite Your Sources

Did you borrow an idea from someone? A definition, an argument, a logical step? Than you should cite it. This is especially true if you are a university student, or writing this paper for a professional outlet like a magazine or journal. Give credit where credit is due. For informal writing, simply pasting a hyperlink in your essay wil usualy suffice. For formal writing, check with the organization you are writing for about their citing requirements and format.

4. Final Thoughts

You've now learned how to recognize and ask questions about your conceptual model, the methods of logic and philosophical thought, how to do research, and how to write. These are all the things necessary to create a well-informed, well-structured, and well-thought philosophy essay.

You now have all the tools! If you've completed all the challenges, then give yourself a pat on the back--you did some very challenging work. But this is just the beginning! There is a world of knowledge out there just waiting to be questioned, researched, and written about; your only limit is your imagination.

I will leave you with one last challenge, to test all of the skills you have acquired.

Challenge

Write a philosophy essay! You may choose to build on the work you have already done in the challenges, or branch out into a new area that interests you. The choice is yours. Good luck!