HOW TO WRITE A PHILOSOPHY ESSAY

By Kyle Strouse

Logical Thought

In the last section, you learned how to ask philosophical questions and came up with one yourself. In this section you'll learn the basics of logic and philosophical thought, so that you can answer your question with reason and rationality.

1. Why Do We Need Logic?

Philosophers disagree about a lot. Time, space, free will, God, even whether or not anything exists at all. Because they disagree so much, it can be hard to find common ground. Without a set of truths and rules that most philosophers can agree upon, philosophical arguments would be reduced to meaningless assertions of opinon. Logic is this set of truths and rules. Primarily, it is the study of reasoning and arguments. Philosophers use logic to develop existing arguments, come up with new ones, evaluate the arguments of others, and draw conclusions.

2. Premises and Conclusions

In formal logic (the logic we are concerned with) the primary tools are premises and conclusions. A premise is a statement that can be either true or false. "You are a philosopher" is a premise. So is "All mammals are humans." A simple declaritive statement like "hello" is not a premise. Neither are statements that cannot be classified as true or false, such as questions. Premises can be symbolized with letter variables, much like varaibles in mathematics. So the premise "all humans are mammals" can be symbolized with the letter p, and the premise "Socrates is a human" symbolized with the letter q, and so on. A conclusion is a statement that must be true if the premises are true. One way of drawing conclusions from premises is a syllogism. A syllogism is a form of argument in which an inital statement, called the major premise, is combined with a second statement, the minor premise, to form a conclusion that must be true. An example of a syllogism might be:

All human are mammals (major premise)

Socrates is a human (minor premise)

Therefore, Socrates is a mammal (conclusion)

The conclusion must follow from the premises because Socrates belongs to the category of humans, and all humans are mammals. This makes Socrates a mammal.

3. Validity vs. Soundness

It is important to be able to distinguish between soundness and validity. An argument is valid only if the conclusion logically follows from the premises. An argument is sound only if the argument is valid and the premises used in the argument are true. All sound arguments are valid, but not all valid arguments are sound. For instance, consider the following syllogism:

All doctors are birds

All birds are insects

Therefore, all doctors are insects

This syllogism is a perfectly valid argument, because the only criteria for validty is that the conclusion follow from the premises. It is not, however, a sound argument, because both of the premises are quite obviously not true.

Challenge

Before moving on, evaluate whether the following argument is sound:

All philosophers are humans

Some humans use logic and reason to answer questions

Therefore, some philosophers use logic and reason to answer questions

If you believe the argument is sound, provide reasons why. If not, explain.

4. If-Then statements

If you answered no to the challenge above, than you are correct--that argument is not sound. While the premises may be true, the conclusions do not logically follow from them. If you answered yes, don't worry--it was intentionally designed to be misleading.

The problem with syllogisms are that they can be confusing and hard to work with. For instance, the challenge questions seems valid at first. Because some humans use logic and reason to answer questions, and at least some humans are philosophers, it should make sense that some philosophers use logic and reaon to answer questions, right? Not necessarily. To help illustrate why, we can make a venn diagram:

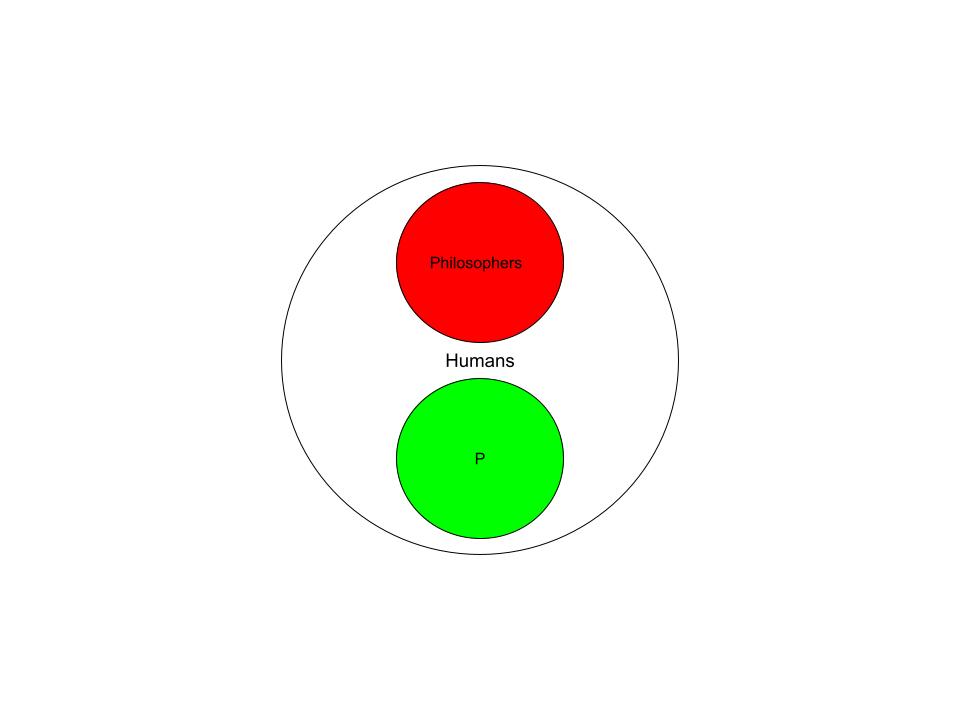

This diagram represents the first premise; "All philosophers are humans". To graph the second premise, "some humans use logic and reason to answer questions" (or p for short) we just need to put p somwhere in the humans section, like so:

Now, notice how philosophers and p are not overlapping. This is because we only know that some humans use logic and reason, not all of them. And because we do not know who these "some" are, we cannot conclude with certainty that "some" philosophers use logic and reason to answer questions, because it is possible that none do (which is what the graph above represents). This is an example of the logical fallacy called the undistributed middle, which occurs when the minor premsie of a syllogism is not distributed completely to the major premise, or vice versa. In our case, if the "some" in the minor premise were to be changed to "all," the argument would be both valid and sound. But as it stands the argument is invalid.

Philosophers dislike working with syllogisms because situations like the one above pop up quite often. Instead, they represent many premises with if-then statements. An if-then statement is simply a logical relationship stating that if one thing is true, another thing must also be true. For instance, instead of writing:

All philosophers are humans

We could write instead:

If you are a philosopher, than you are human

Likewise, to write the major premise as an if-then statement we would change:

Some humans use logic and reason to answer questions

To:

If you are a human, than you either use logic and reason to answer questions or you don't

These if-than statements help reveal the flaw in the argument that was hidden in the syllogism--namely, that being a philosopher does not necessarily imply being a human that uses logic and reason to answer questions. Because they help reveal logical inconsitiences, it is good practice to translate logical arguments into if-then statements whenever possible.

5. Logical Operators

Logical operators are simply ways in which we can modify the truth values of premises. You use them all the time, everyday. The ones that we will cover in this tutorial are conjunction, disjunction, and negation.

Conjunction

Conjunction in English and informal logic is represented by the word and. Conjunction takes two or more values, and as long as each value is true, the premise it forms is valid. Think of conjunction like a chain--so long as each link in the chain is present, then the whole chain will also be present. But if one link is missing, then the whole chain will fall apart. Some examples of conjunction are:

- John and Sally both went shopping

- I am going to eat dinner and watch a movie

- Socrates and Plato and Aristotle are wise

In each of these premises, if one of the values being conjuncted is false, than the entire premise is false. For example, if it turns out that Socrates is not wise, but Plato and Aristotle both are, then the premise still returns false.

Disjunction

Disjunction is represented by the word or. Disjunction, like conjunction, takes two or more values, and returns a true premise so long as at least one of the values is true. Disjunction returns a false premise only if each value is false. Examples of disjunction include:

- Either Peter or John are helping me with homework

- They are going to the concert or the play

- Descartes or Spinoza or Leibniz are wise

In each of these premises, so long as one value is true, then the whole premise returns true. For instance, even if it is false that Descartes and Spinoza are wise, the whole premise is still true as long as Leibniz is wise.

Negation

Negation is represented by the word not. Negation takes one or more values and returns true if the value(s) is (are) false. Negation returns false only if the values it takes are true. Some examples of negation are:

- Isaiah is not looking forward to the quiz

- Augustus Ceasar and Julius Ceasar were not salads

- Descartes or Spinoza or Leibniz are not wise

So long as the value (or values) being negated in each sentence are false in each of these premises, then the value is true. So, for instance, if it is false that Descartes is wise in the third example, then the value for Descartes returns true. And, since a disjuncted premise requires only one true value to be wholly true, then the whole premise is true.

Conclusion

Now that you're familiar with the basics of logical thought, you can start to rationally analyze philosophical arguments made by others and construct arguments of your own. We will learn how to do both in the next two sections. Keep in mind that the logic covered in this section of the tutorial, while important, is extremely basic. To enrichen your knowledge of logic and strengthen your philosophical abilites, consider picking up an introductory textbook on formal logic. A great free resource for learning can be found here.

Challenge

Before moving to the next section, it's a good idea to apply what you've learned. Analyze the following argument by: a) identifying all the premises; b) identifying all the logical operators; c) determing if the argument is valid; d) determing if the argument is sound.

All experiences that humans have are derived from the stimulation of the senses. For instance, our experience of vision is simply a sense-organ (the eye) reacting to some stimulus (light). This is true of all experiences. If all our experiences are derived from the senses, then it is impossible to know anything other than what our senses tell us. If we only know what our senses tell us, then objective truth must be either beyond our senses or else it does not exist. But we do not know anything beyond our senses. Therefore, objective truth must not exist.